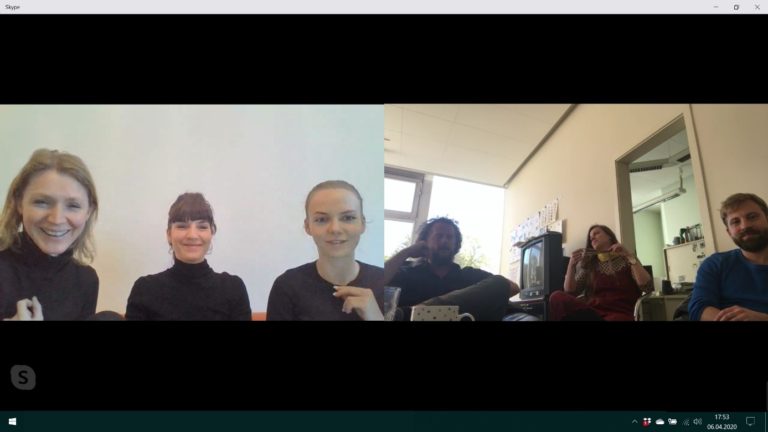

Rückkehr in die 1960er Jahre: »Cinerama«-Format und Split Screen bei der Bühnenbildabgabe von »Kitesh« (v.l.n.r.: Franziska Kronfoth, Christina Schmitt, Maria Buzhor, Florian Lutz, Ann-Kathrin Franke, Maximilian Grafe)

Does anyone remember the time when cinema was still produced mainly for the screen? After the recording process of the Cinemascope, the even wider “Cinerama” had been developed in the early 1950s. The idea behind these formats was to create a feeling of width. Inevitably, however, they were then drawn into the newer medium of television, where they created a rather claustrophobic feeling of unease: stagecoaches or Roman chariots – tiny, they chased along within a narrow strip of film surrounded by black bars.

Back in the days of Cinemascope, we seemed to be these days, since interpersonal relationships are only disembodied via the zeros and ones of digital communication, when the »Kitesh« stage set is given in Halle. And there, too, it was now, behind the scenes, mainly about questions of format.

Almost always over the past hundred years, the theatre’s developmental thrusts have taken their starting point in the intimate setting of smaller venues. Only here, where the actor and the theatregoer come close to each other in a small audience and a vibrant field of conflict between the real and the fictional arises, could – and perhaps had to – create a new aesthetic that, with the sophistication of illusion theatre, also pushed the separation of the spheres between artist and audience overboard, bringing the visitor into the play and understanding him or her as a participant.

But what happens when such a theatrical approach, as it remains decisive for Hauen und Stechen, encounters the machinery of the municipal theatre, whose architecture alone is already oriented towards a contrary idea and whose directors, halfway understandable, are still measured by their employers in terms of capacity utilisation payments?

For this reason, the houses of Halle, Wuppertal and Bremen still insist on two hundred visitors per performance at “Kitesh” – and that is quite a compromise. But it’s difficult for Hauen und Stechen to make the theatre under these conditions with which they have made a name for themselves as a group.

That’s why “Kitesh” still has the houses of Halle, Wuppertal and Bremen insisting on two hundred visitors per performance, and that’s a compromise in itself. But it’s difficult for them to make the kind of theatre under these conditions with which they have made a name for themselves as a group.

No more typical feXm conflict could be imagined. Two systems that have so far been incompatible, analogous to those used in the early days of cinema and television, collide here. As in the case of the film and monitor format (one less wide today, the other wider than before), city theatres on the one hand, and free scenes on the other, will be forced to take new paths, but this should not be a separation that fixes both on outdated patterns.

However, anyone who, thanks to all the current screening of historical performances and video transmissions from deserted auditoriums, follows the theatre of these days on their PC will learn that the stage here is like Peter Schlemihl, who sold his shadow. With rapid changes in location and the alternation of close-up and distant perspectives, film has become an art form in its own right, one that still has little in common with theatre. Unintentionally, all the compensatory performances with which the stages try to keep their audiences in line reflect above all the untransferability of the theatrical experience into the digital world and thus the full depth of the momentary loss. Not only must the speech and action of even the best stage performer appear hollow and exaggerated when they appear in a foreign medium. In reaction to the language of film, theatre also had to reflect on what it has ahead of film. The concept of the separation of audience and actor belongs to film today. However, no other art is so beaten by social distancing as that of theatre.