Nayun Lea Kim not in the role of the "Fan", but in the role of the gamer of the "Fan" avatar. Photo: Sascha Kreklau

Successful premiere of “Freedom Collective” at the MiR. Where have we got to from my point of view?

Davor Vincze’s score is certainly the most challenging that the theatres have ever had to deal with as part of NOperas! Fears that the agreed number of orchestral rehearsals would not be enough were not realised at the MiR: Premil Petrović – as musical director from out of town and also part of the project team – was impressed by the commitment and virtuosity of the Gelsenkirchen musicians after the very first rehearsal. He was equally full of praise for the perfectly cast quartet of four singer-actors. And hats off to the MiR’s sound department for the seamless spatialisation of the sound and for the perfect amalgamation of live musical events and electronic playback.

Davor Vincze has also written by far the most “operatic” NOperas! score to date, including, one is amazed, a love duet that is hardly inferior to Der Rosenkavalier in terms of culinary delights. Pathos and beautiful sound, which for a long time were definitive “no-nos” for composers who did not want to chum up to the music theatre business, are finding new honours. But every sound remains advanced. His music never falls back into the epigonal or harmlessly eclectic. Where is the difference between the real and the unreal, between statement and irony and quotation? I am still struggling with it.

Now, the name of the NOperas! programme includes the word “not” alongside “opera” – it is intended to be about projects that also break new theatrical ground. Projects that, in whatever way, go beyond the traditional narrative of the opera genre. When awarding the project, the jury expected this above all from the concept of using smartphones to involve the audience in the musical theatre experience. In most people’s opinion, this was only partially realised, at least in this first stage of the project at the MiR. For some, their browser got in the way. Those who were “connected” instead hardly experienced anything additional in terms of substance. One woman I spoke to, who must have been barely thirty, even reacted allergically: “I’m going to the theatre to finally get away from this thing, but even here everyone is fiddling with their mobile phones now!” If this complaint is essentially also directed at the NOperas! jury, then the demands to involve the audience as actors in the theatre events already had to be scaled back in the end with “Chaosmos”, the first NOperas! production. The idea of gamifying musical theatre is currently on the minds of many. Rarely have I seen this goal achieved in a convincing way. But Bremen and Darmstadt are still waiting here.

The fact that even the first development stage of “Freedom Collective” fulfils the claim of NOperas! is due to Heinrich Horwitz’s approach of not telling stories in the conventional way. The audience is not tied to seats. Fuzzy Edges separates the stage and, as it used to be called, the “auditorium”. The art form is not that of an opera. It is that of an environment of light, sound and rather symbolically withdrawn theatre action. A meta-level does the trick: the four performers do not embody characters in the play, they are players who lead these characters as avatars. But it is a game, even if it is primarily narrated. Nonetheless, the audience should remain active. Vincze’s score provides support by – a key moment – breaking out of the operatic idiom into electronic dancefloor sounds for an extended period in the middle of the piece. Some let themselves be carried away by the ensemble as animators to rave. Others seemed rather irritated, at least on this premiere evening, barely overcoming their inhibitions about desecrating the MiR’s opera temple in the desired manner.

The evening was sold out and the average age was a good half that of normal opera evenings. A striking example of the fact that music theatre needs new forms and probably also new formats if it wants to reach younger audiences in future. Most of them simply gave in to the pleasure of “media overkill” (Deutsche Bühne). Provided they had realised that the sung text often refers to drugs, they experienced an intoxicating evening even without them. Vincze’s music, however, tells a story with many plot twists at every moment: Who fights whom, who loves, who betrays whom, what happens to whom and why? Others’ eyes are glued to the surtitles, which unintentionally re-establish the usual separation between stage and auditorium, theatre and audience. You try to decipher plot conflicts that are not important to the scene, get stranded in the process and end up feeling fooled.

Rarely have I heard such different voices as after this premiere. It achieved something decisive when it led to such lively discussions. As a NOperas! project, I feel that “Freedom Collective” lives essentially from the deliberate dialectic between Vincze’s revival of genuine operatic drama and Horwitz’s theatrical post-drama. The latter has so far retained the upper hand.

The almost complete Dritte Degeneration Ost in Stralsund (only Richard Grimm, the composer, is missing). From left to right: Romy Dins, Antonia Beeskow, Anne Bickert, Frithjof Gawenda, Frieda Gawenda, Laurenz Raschke, Mathias Baresel (Photo: Roland Quitt)

The new year begins for Dritte Generation Ost with an intensive working retreat at OPER OTZE AXT in Stralsund. Three of the eight come from there, the mother of the two Gawendas gives up her flat and it becomes a NOperas! flat share for a week.

One week of hard work. The daily schedule is rigorously organised. In the mornings, the team splits into smaller groups to work separately on individual areas – libretto, stage, music – and bring them back together in the evening in a plenary session. Additional funding organisations apart from feXm are also researched; the plan is for the project to continue to develop after the end of its three NOperas! phases and to be able to find additional performances, especially in the East.

During the last two working days, I join the feXm as dramaturge. Outside it’s freezing cold and the sky is bright blue, in the Gawenda flat there are overflowing ashtrays and thick clouds of tobacco.

A number of fundamental ideas have emerged during these days.

OPER OTZE AXT is roughly based on the real life story of Dieter “Otze” Ehrlich. It should remain inspired by his story. It should remain inspired by Ehrlich’s story without retelling it in detail and without laying claim to historical truth. Under no circumstances should it follow in the footsteps of the well-written personality musicals à la Lindenberg, Bowie or Abba.

Basic stages: Otze as a non-conformist, his rebellion, his conflict with state power and his secret pact with it when he becomes an informer for the Stasi. Otze then in the united Federal Republic of Germany: he slips into drugs, he kills his father.

Somewhere hidden in this story are questions about the relationship between the GDR and the new unified Germany. About the so-called “Wende” years, about the punk movement in East and West. And, of course, questions about the concept and idea of freedom. “Break what breaks you!” sang Ton, Steine, Scherben at the time. “Why don’t you break yourself!” was the title of a song by Dieter Ehrlich.

Although DDO has an equal number of male and female members, these two days are all about the male world. Of tough guys who get into heroic fights and get drunk, conspiratorially building their amplifiers somewhere to shout out their frustration in the closed-off world of the punk community.

Three protagonists emerge: Otze, his father and the collective of a many-faced and therefore all the more faceless conformist outside world – as character masks and voice leaders of the “Germany” system (first East, then East-West), individual figures can emerge from it, only to immediately fall back into it again. In any case, women do not seem to play a decisive role in Othete’s world. To be Oedipus, Otze has so far lacked Iocaste.

How does music theatre that refers to punk go together with classically trained opera voices and the instruments of a classical orchestra?

The key figure should be that of the father, conceived as a person who is always present but always silent. He is surrounded by the absence of sound. Silence is one of the most powerful means of musical expression at the moment of the general pause. Rebellion through noise and sound, on the other hand, characterises the son. While he cries out in vain for dialogue with his father, both are speechless in their own way. The idiom of the opera is then parodically set against them both as that of a West-Eastern petty bourgeoisie trapped in musical clichés.

It is above all this musical dramaturgy that has so far provided a more precise interpretation of the Otze parable. A play, therefore, about the speechlessness of an all-German society. A play also about the changed continuation of the parental conflict of 1968 into the 1980s.

While the revolt of the 1960s was as optimistic in its belief in the possibility of a better life as it was saturated with language and theory, after the collapse of all this hope, after the end of the Prague Spring in the East, the RAF and the Red Brigades in the West in the later Honecker era, which was also the era of Kohl, Reagan and Thatcher, all that remained was the language- and theory-less feeling of a last dance on the Titanic. In “contemporary music”, all binding systems disintegrated during this period. Pop is indulging in gloomy, plaintive songs. Punk cries out against the world without being able or even wanting to show a better one. Only the Gorbi shouts put an end to the general feeling of no future. But in Kohl’s blossoming landscape, the AfD is thriving today.

At the NRW KULTURsekretariat in Wuppertal: almost the entire feXm jury this year. From left to right: Christian Esch (feXm), Søren Schuhmacher (Darmstadt), Rainer Nonnenmann (external juror), Michael Schulz (Gelsenkirchen), Kirsten Uttendorf (background; common voice with S. Schuhmacher), Brigitte Heusinger (Bremen). Not to be seen: Moritz Lobeck as another external juror, who could only be connected via Zoom. © Roland Quitt

Two jury meetings are needed to decide on the next NOperas! project based on the applications. As always, a group of finalists was selected in the first session, who then had a month to contact the participating theatres, ask more detailed questions about the opportunities available there, and concretise their own plans in more detail, in order to then face each other face-to-face in a more in-depth discussion in the second session.

As is almost always the case, this time the decision remained difficult until the last moment. “Oper Otze Axt” is the name of the project that won the race. The collective responsible for the production is called “Dritte Degeneration Ost”.

“Oper Otze Axt” is inspired by the life of Erfurt punk musician Dieter “Otze” Ehrlich and his band “Schleimkeim”, which was part of the musical underground of the GDR. The team convinced the jury, among other things, by placing its particular view of the German-German problem against the backdrop of the reunification years, provocatively generalising the question of the nature of freedom beyond this context and thus making an intelligent thematic contribution to pressing contemporary issues within the framework of musical theatre.

“Dritte Degeneration Ost” is not only the largest collective (eight people share artistic responsibility), but also the youngest to be awarded the feXm contract. The name satirises the attempts to come to terms with German-German history by the “Dritte Generation Ost” (Third Generation East) network and association. Almost all of the team come from the “new federal states” and link their project to coming to terms with their personal experiences. But even more than the “Third Generation”, the “Third Degeneration” belongs to the post-reunification period, looking at the time from the perspective of an experience that is still close enough to be of personal interest, but distant enough to create a new historical perspective.

Screens with techno thunderstorms at the "Freedom Collective" mock up set rehearsal © Roland Quitt

The word “reality” is replaced by “realities” in the play description written by the team. There is no longer just one. More or less assuming that it is hopeless or perhaps simply no longer a question of separating the true from the false in the conventional way, of recognising the idea of multiple realities.

Each person should experience their own piece in this “immersive” music theatre. Everyone should be able to move freely through the theatre in a space that is both stage and auditorium at the same time, thus eliminating their conventional separation.

Everyone should drift between different interpretations of the plot, none of which is more correct than the other.

Immersion, however, proves to be a difficult exercise when it comes to musical theatre with highly complex music and a correspondingly traditional orchestral set-up. The rehearsal in Gelsenkirchen was also aimed at solving such problems. The spaces in the three participating theatres are different. Magdalena Emmerig has created flexible room elements that can be adapted to the respective circumstances. The opera directors and technical departments of all the theatres involved had travelled to Gelsenkirchen. For them, Gelsenkirchen also became a kind of test case. Would it be possible to find solutions here that would bring everything under one roof for them too?

Screens dominate our lives for years. Corona has multiplied the trend: Zoom conferences have taken the place of city trips or even travel, Netflix has replaced theatre visits, virtual sex in 3D has replaced real contact tracing. Theatre is a space of physicality. Screens will also define “Freedom Collective” – large ones in the auditorium, small ones on the mobile phones involved in the performance. But visitors will become co-actors. They will not only have to move around the space, but will also be challenged to perform their own “physical” actions on their mobile phones and ultimately experience a split world of feeds (also on a musical level) and live events.

The sound technology involved – the famous SWR experimental studio, without which the works of Luigi Nono, among others, would not have been possible – will probably not always make it possible to recognise which sound is coming from where. All the more, however, it seems to be about the tension between what is mediated and what is experienced as “live”.

So aren’t there perhaps criteria by which we can filter the jumble of divergent “experiences of reality”?

Ende der Gelsenkirchener Fundstadt-Aufführung: Kinderstimmen und klangliche Reminiszensen driften durchs Foyer (© Roland Quitt)

2 June: Premiere of “Fundstadt” in Bremen / 16 June: Premiere in Gelsenkirchen. The reviewer of the Bremer Kreiszeitung describes the performance as “magical”. Fundstadt’s claim to “let us see the world through a child’s eyes”, he says, initially seems “a bit kitschy”. One of its greatest assets is that it has escaped all kitsch. Just as the team met the children involved at eye level, so now does the audience. The “beings” that the six children invented for themselves as companions appear threatened in quite a few cases. “They want to break you” says Ali to his, which he hides in a shoe box. He promises him to protect it. “The truth is not always the most beautiful” speaks the voice of a girl from Bremen from offstage (most of the time she is downright “disgusting”). She wants to become a veterinarian. But what if an animal got into trouble and a friend needed her help at the same time? There would then be no right thing to do. So she has decided to do without friends in her life. Salvation is not one of these children’s worlds.

Where sound does not oppose the visual in music theatre, it runs the risk of becoming bogged down in the subconscious. The six films do not escape this either. In front of the film image, the music liquefies into a soundtrack in places, although it deserves to be heard more consciously. The live actions, created by children and instrumentalists, compensate for this. Their visual and sound memory motifs bring back the images and sounds of the film.

The six filmic portraits of children remain the same in both cities. Three in each city link directly to the place where they are seen. The live actions differ only slightly as such in both cities, but change their character with different spatial placement. The surfaces of shimmering gold paper – they refer to film in a shoebox – seem lively in the Gelsenkirchen sunshine, magical in the Bremen pedestrian tunnel.

The short finale, in which the live children interact with the audience, took place in Bremen in the theatrical atmosphere of the Brauhaus stage there. Colourful light illuminated irregularly placed crumpled chairs. If in Gelsenkirchen one had been one of the first to finish one’s way, in the upper foyer of the MiR one encountered thirty cots arranged in a strict row, as if Beuys had been reborn to counterpoint Yves Klein’s wall space. The irritation of “what is actually theatre here and what perhaps simply belongs to the world” (Bremer Kreiszeitung) was not resolved here, but symbolically heightened once again by the wide view through the glass window of Gelsenkirchen as a found city. When thirty people then lay lined up on the cots, they appeared like the wounded in a military hospital. Children appeared above them as doctors. They looked up at them from their cots and the little ones were suddenly the big ones. One after the other, they turned their attention to each patient, exchanging a glance with him through a hand mirror.

Heinrich Horwitz in the small house of the MiR © Emmerig

“Fundstadt” is in the middle of the final spurt and “Freedom Collective” is picking up speed. Often in May or June, two feXm production teams find themselves at the same venue. While HIATUS is working on the rehearsal stage of the MiR, a few rooms away the departments meet for the first conversation with the people from “Freedom Collective”. Heinrich (director) and Magdalena (stage) were still in Bremen yesterday, Darmstadt will follow next week. The idea is that the audience should be able to move freely during the performance. Each stage offers different constraints, each also different possibilities. The idea is that the audience will be able to hear equally well from everywhere – and this will require a lot of effort on the part of the sound departments. In addition, there is the challenge of the smartphone network, which provides additional input to what is happening on stage. The orchestra line-up has been fixed in the meantime. The final determination of the vocal parts is now pending. All the theatres should be able to cast the vocal parts from their own ensembles, if possible; guests will hit the production team’s own budget. Within the team, the staging has to be balanced with the music. Davor (composition) answers from Lyon, where he is spending the first of his two weeks at GRAME (Générateur de ressources et d’activités musicales exploratoires) and is already busy working on the level of electronic feeds.

© Roland Quitt

NOperas! sets itself the task of bringing forms and ways of a new music theatre to the municipal theatre. However, the operations there are still geared solely to classical music theatre narrative forms. The interviews in Wiebke Pöpel’s film documentation of the last NOperas! project beautifully illustrate not only the irritations that this always brings for both sides, the municipal theatre and the actors of the independent scene, but also the necessity for mutual adaptation and learning from each other. How can orchestral musicians and children work together if the orchestra union only allows working hours when children are either at school or in bed for the night? This was the problem faced by “Fundstadt“. No one can be ordered to perform such services. Everything can only succeed through individual persuasion and a willingness to generously navigate past the existing rules.

At the main rehearsal in Bremen yesterday, many of the musicians and children posted around the city found only an astonished and at the same time uncomprehending audience of random passers-by. A mistake had crept into the sequence of photos that were supposed to serve as signposts for the actual test audience on their tablets – more than half were soon wandering disoriented through the city past the stations. In such situations, the theatre adheres to the firm belief that it is not a good omen for the premiere if final rehearsals go too smoothly. They fiddled with the tablets until four in the morning, and today at the dress rehearsal they all found their way. The golden apparition who met me in the pedestrian tunnel pushed me against the wall and then informed me (in a child’s voice): “I know everything, EVERYTHING about you!”. Everything really? Oh God! Little reassuring then was the further information: “You will die a VERY cruel death!” The gold being, Uta Plate then told me, pulling out her correction slip, had not been instructed to address me in such a nightmarish way. I advised her not to intervene. The tunnel sibyl had nothing nice in store for my companion either: “You’ll spill your coffee tomorrow morning!” In any case, misfortune remains relative! For tomorrow, we can only hope for a change in the November temperatures in Bremen.

Jason's desk © Hiatus

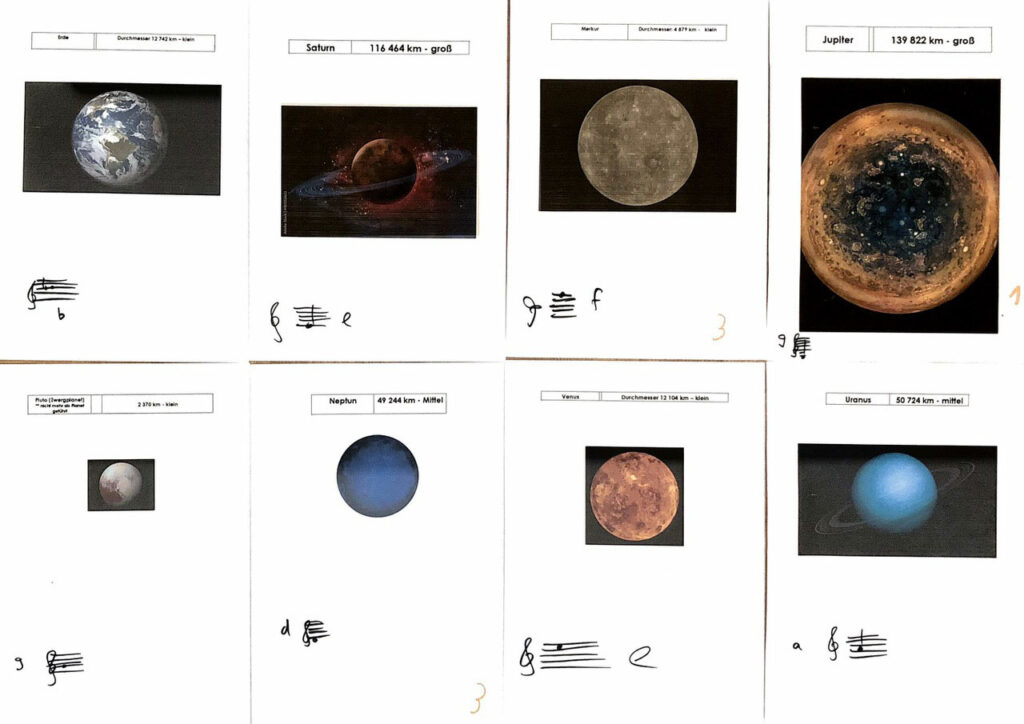

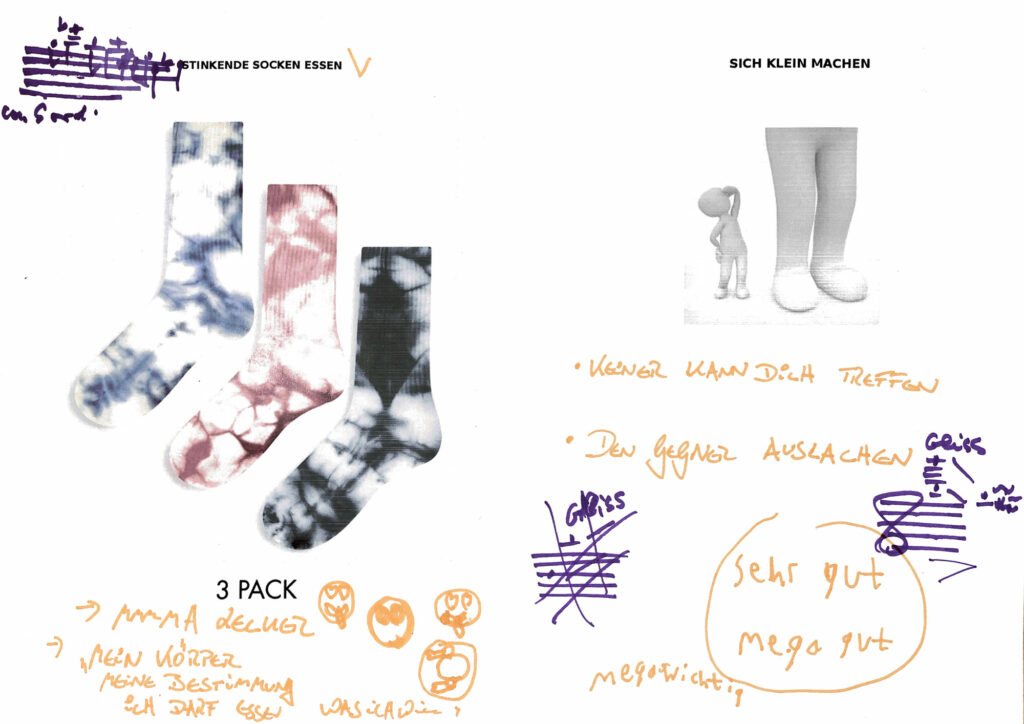

Fundstadt enters the final spurt. The production team described this project in its application as an “urban topography of two cities from the perspective of children from socially different backgrounds”. Three children each from Gelsenkirchen and Bremen have worked and continue to work intensively on the project. In the meantime, they have all invented their own “thing” equipped with essential features, which according to their specifications is now being built in the workshops. Together with musical patrons from the respective orchestras, they have also composed the “thing song” assigned to their thing, which is now being recorded by instrumentalists from the orchestras in various chamber music formations. Each of the children will have their own station on the path that the audience will have to travel. The six children themselves, their objects and things will be components of the digital events, which will be called up at these stations via tablets. Along the way, you will also encounter live musical theatre actions, for which other children and other orchestra musicians have come together. One of the six film children is Jason. Hiatus wrote the following email to the Gelsenkirchen performers inside of his thing:

“Dear Mariana Hernández González,

dear Istvan Karacsonyi, Gioele Coco, Rainer Nörenberg, Uwe Rebers,

you are the DINGLied ensemble of Jason, we are happy to be able to experience you! Jason’s being is a creature from another planet made of red sand. It has four hands, two human ones, two crab claws, and on its head it once again wears bones to protect it from attacks. It can walk up walls and run upside down on the ceiling, it can make itself big and small, shoot lightning. Its favourite food is stinky socks. In the film, Jason virtually creates his own world. He starts in an empty white room and sets up his workspace in a garage, building his own solar system. One day he comes back to his studio in the garage and finds it transformed. There his being appears to him. Jason does not know whether his world has continued to build itself in his absence and thus the being has come into being, or whether the being has continued to build secretly. In the last music meeting with Jason, we laid the foundation for Jason’s DINGLied with the help of Jason’s fantastic “music godfather” Istvan Karacsonyi. Jason invented music patterns with the nine planets of our solar system. There are also settings by Istvan of the creature’s superpowers (see appendix for an example). The music will build up gradually in analogy to Jason’s film story.”

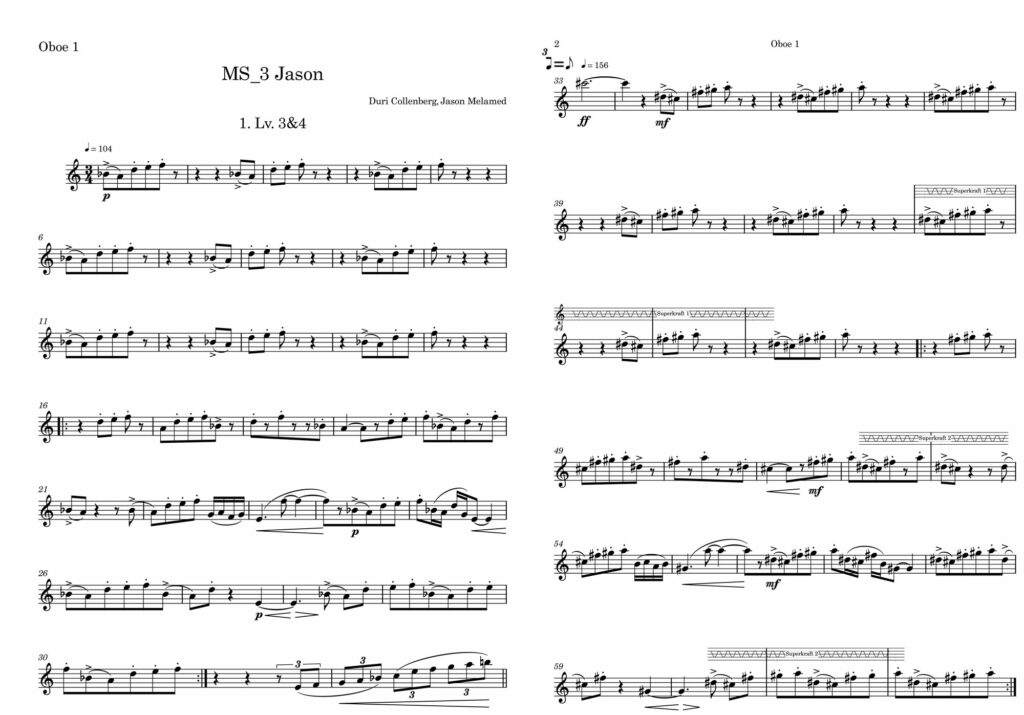

Duri Collenberg has developed a playing score for Jason’s Dinglied, the various parts of which are appended to the letter – below here: the notes for 1st oboe.

Stills from the film version of the short opera "Xinsheng" (Director: Heinrich Horwitz)

The project for the 2023/24 season has been fixed since October, and now finally its definitive title – “Freedom Collective”. Since December, the more precise plot outline has been in the making. For his preliminary compositional study (still titled “XinSheng”), Davor Vincze, together with Rama Gottfried and Andrés Nuño de Buen, received the renowned annual Stuttgart Composition Prize last weekend. More than 150 compositions had been submitted as applications. The three prize-winning pieces, which were premiered at the closing concert of the Stuttgart Eclat Festival, could hardly have been more different – Nuño de Buen’s guitar quartet: spare, restrained, almost hermetic; Gottfried’s “Scenes from the Plastisphere”: playful and open in form; “Xinsheng”: culinary, refined, with tonal delicacy and a grand gesture that does not shy away from the operatic. The ensemble Mosaik played with clarinet, cello, keyboard, percussion and (yes, this instrument really exists:) electric zither; Nina Guo sang. The sold-out auditorium applauded. We eagerly await the further progress.

Duri Collenberg, Ali (© Uta Plate)

Musical theatre companies are highly specialised businesses, set up in all their processes for the classical opera form. Every NOperas! production creates challenges, and the most difficult ones can arise when they affect the orchestra. Children are supposed to work on compositions together with orchestra musicians in “Fundstadt”, but in the mornings children are at school, in the evenings they are asleep, and in the afternoons, as the union wants, musicians are not allowed to work, even if they want to. After a lengthy tug-of-war, this problem is now also off the table. Also, the performers of both orchestras are now in place.

During two workshops in Gelsenkirchen and Bremen last year, HIATUS recruited the six children around whose lives, dreams, hopes and self-composed orchestral music “Fundstadt” revolves. While other children will be involved in the theatre action, these six will only appear for the audience on the tablet feeds. In a second workshop phase, it was not only a matter of entering the life worlds of these six “film children”. Uta Plate and Duri Collenberg write:

“Our stay in Gelsenkirchen and in Bremen during the last two weeks was predominantly marked by the encounters with people with whom we will be, and in some cases already are, immersed in the artistic, content-related work for “Fundstadt”.

o The children: We visit all six film children individually, they take us on a long walk through their everyday lives. This leads from family to school, from religion to leisure, from the visible to the imagined.

o The musicians: There is a first personal conversation with colleagues from the Bremen Philharmonic Orchestra and the New Philharmonic Orchestra of Westphalia. In March, the work of developing the music begins; many ways have to be tried out in order to get from the children’s ideas of sound to a form that can be realised by orchestral musicians. The instrumentalists involved are to be involved in this process from now on.

o The people around the theatre in Bremen and Gelsenkirchen: With the filmmaker Aaike Stuart we visit places to which the walks with the children have led us. There are first tests of film sets, small test shoots with the children. For the route of our walk, we then find places near the theatre that are representative of the everyday and fantasy episodes of the film children as “stations” of the audio-video walk. In the process, we have spontaneous, wonderfully sympathetic meetings with local residents, petrol station owners, garage owners, directors of an old people’s home, whose participation will enrich the diversity of the stations of the walk and the film recordings.”